The History of Carmignano

The World's Oldest DOCG

by Walter Fortini

The fame of Carmignano as a wine is an inextricable part of the entire history of the township. In its aroma, its flavour, its perfume are hidden the many stages of the development of its culture, from the very first days of the settlements which came to characterize the zone. The discovery of vessels of wine inside Etruscan tombs and the fact that Julius Cesar, between 60 and 50 B.C., assigned certain areas between the Arno and Ombrone rivers to veterans of his campaigns, land which has been planted to vineyards ever since, gives some idea of how long this history is. The first written records to document the production of wine and olive oil on these hillsides, however, are centuries later, during the period of Frankish dominion in 804 A.D.

They date to the reign of Charlemagne and his son Pipin, and the parchment, written in Latin, which contains a contract in which the church of San Pietro a Seano, concedes the use of its land on the hillside of Capezzana, describes “vineis, silvis e olivetis”: vineyards, olive groves, and woods. These were rented out in an agreement which can be considered a type of sharecropping before that kind of arrangement formally existed.

It is not possible to express any sort of opinion on the quality of the wine of that period, but already in the 14th century we can find a judgment of this type on Charmignano, as it was then called. Francesco Datini, merchant in nearby Prato, writing to a notary, Ser Lapo Mazzei, ordered 15 soma – approximately 1500 liters, or 400 gallons – of the wine for his cellar. This famous businessman of the period, well known for his keen commercial sense, was willing to pay “a florin” per soma, four times the price of the most prestigious wines of that period, for Carmignano. Evidently he had his own good reasons for doing so. Another 14th century figure, Domenico Bartoloni, also spoke of “the excellent wines of Carmignano and Artimino”. Three centuries later, in his famous dithyramb, Bacchus in Tuscany, it was Francesco Redi who sung the praises of these wines.

“If I take a vessel of brillant Carmignano in hand –

declaimed the poet – My chest so swells with joy,

That I feel no envy for the ambrosial nectar of Jove “

The dithyramb was an ancient form of choral poetry used

to celebrate the orgiastic rites of Dionysus, the Greek god of drunken frenzy. Francesco Redi, physician, and a

favourite poet of the Medici, who also recounted anecdotes

of other leading personalities of that court, imagines Bacchus (the Latin name of Dionysus), intent on sampling all of the wines then known. Such French wines as Clairette of Avignon are undoubtedly famous, he says, and Chianti as well, which is an impeccable wine. But the wines of Artimino and Carmignano, he lets us clearly know, are something on a different level. And the judgment is an authoritative one: it issues forth from the mouth of a god.

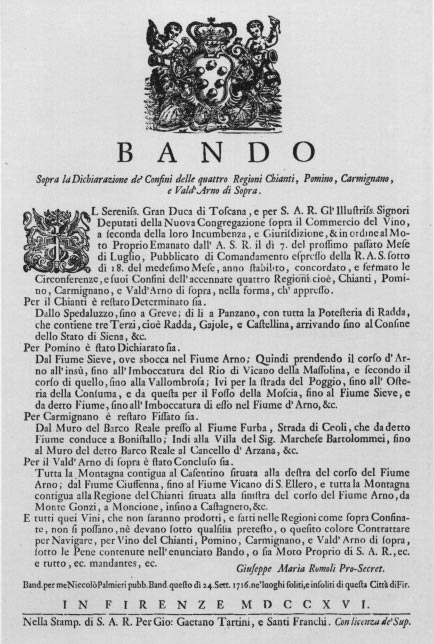

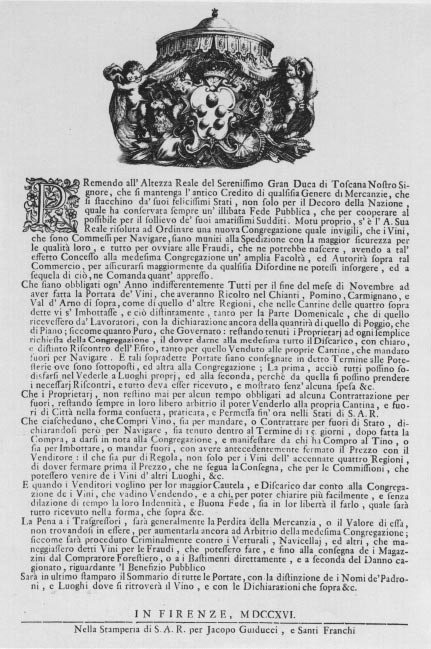

This outstanding wine, a perfect match for roasts and for game, capable of being aged for a very long time, conquered a very important position in the markets of the time, to the point, in fact, that in 1716 Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici issued a proclamation, and then an edict, which established precise and rigorous rules for the harvest and established the boundaries of the zone where the wine could be produced. This was the first example of an appellation wine (it was well in advance of the French appellation controlée system) and, at the same time, conferred noble rank on the wine of Carmignano: only three other Tuscan wines of that period (Chianti, Pomino, and the upper Arno valley) earned similar recognition

From that moment on, praise of Carmignano has never ceased to flow. Lami, in his Lessons of Tuscan Antiquity, cites Artimino for its excellent wine, olive oil, and game”, in addition to the healthy air and the convenient nearby presence of the Arno river. In the 19th century, to cite a few other comments, Repetti – writing in 1833 – affirmed that Carmignano was one of the best, and most renowned, wines of Tuscany, while Amati, in his Geographical Dictionary of Tuscany of 1870, simply used the word “exquisite” to define the wine. When we come to the twentieth century, it would be well to remember the words of praise of poet and novelist Gabriele D’Annunzio.

It is possible that the writer came to know this wine during his high school days at the Lycée of nearby Prato (or that he first sampled it somewhat later when, according to what is recounted, he visited the Gramatica sisters – famous actresses – , the finest interpreters of “The Daughter of Jorio” and, for this reason, heavily courted). In any case, it is an incontrovertible fact that, in the “Hammer’s Sparks”, the name of Carmignano is used on more than one occasion and the author, searching back into his childhood

memories, also describes the quality and sensations of the wine. He wrote: “my father drew off the wine, fragrant with the aroma of violets, and he is very happy this year with his Carmignano, which he first ripened in the vineyards of these hillsides in order to give them a true Tuscan character even before he infused a true Tuscan character into his first-born son”.

Unfortunately, the viticultural history of Carmignano is also studded with missteps and major mistakes in judgment. In 1932, seven different types of Chianti were given official recognition by

the Italian government, among them the Chianti of the Montalbano area, and the entire Carmignano area was shoehorned into the Chianti appellation, forgetting – a great injustice – the entire tradition

of the wine. And it was not simply a question of history and tradition. The presence of various grape varieties, little cultivated or completely unknown in other parts of Tuscany, gave these wines an entirely different personality, from that of Chianti. It should be pointed out, in fact, that Carmignano has always been characterized by a significant percentage of Cabernet which, unlike other Tuscan (or even French) wines made from this grape does not give any herbaceous or vegetal notes to the wines.

The use of Cabernet, now very fashionable, goes back a very long way, to more innocent times when this wine was rarely encountered in the zone and was surely anything but trendy. It has often been written that it was first planted in Carmignano when Catherine de’Medici was queen of France, and on her express orders, and this can be confirmed by the fact that the variety is often called “the French grape” by the older cultivators of the zone, who often had difficulty in calling it by its real name, one which would give away its true origins.

But climatic questions also have a role in distinguishing the wines of Carmignano from those of Chianti, even if the soil is not particularly different from that of other parts of Tuscany. The scarce rainfall during the growing season, usually limited to the last month before the harvest, gives the area its own special micro-climate, not at all dissimilar to that of Bordeaux, where the stony soils drain away the water which falls during rainstorms very rapidly. And the greater luminosity of these hills compared to other parts of Tuscany is another contributing factor in forming the wine’s distinct personality. Accordingly, in the 1960’s , various estates in the zone decided that it was time to return to the true name and origins of the zone. A few years later, in 1971, the Congregation of Carmignano was formed, an association which, in its name, renewed the links to the 1716 edict of Grand Duke Cosimo de’ Medici. The obligatory submitting of the wines to a special tasting commission before commercial release anticipated, in fact, a requirement made legal binding for all Italian wines which aspired to DOCG – a controlled and guaranteed appellation – status. It was precisely this organism – the Congregation – which, in 1999, by then reorganized as an official Producers’ Consortium, was assigned the task of carrying out the official controls on the production of wine in the zone. And it was the Congregation which demanded a true autonomy for Carmignano and began the legal procedures for recognition of Carmignano as a zone, an appellation, on its own. In April of 1975, the ruby-colored wine of Carmignano, which, with age, took on garnet and amber tones, was given its own appellation (DOC) and was allowed to back-date this recognition to all the wines produced from 1969 on. Then in 1990, in recognition of its outstanding character and personality and to include Carmignano in the Burke’s Peerage of Italian wine (at that time nine wines, now nineteen, an increase in number which could even be defined as excessive), this red wine was promoted to DOCG status, a move again backdated, this time to include all the wines produced after 1988. There was no problem in the fact that, at the time (and even now), Carmignano was the smallest zone to enjoy this type of recognition. Quite the contrary: the limited area of production guaranteed uniformly high quality in the absence of less suitable soils and positions and secured a place for the wine for discriminating and informed palates. The production zone, in fact, has remained that delineated by Cosimo III de’ Medici in the eighteenth century: 240 acres (100 hectares) in 1975, which now have become 370 acres (155 hectares) and could eventually become 480 (200 hectares). Part of the zone is in the township of Carmignano, a smaller part in Poggio a Caiano, and the vineyards are on hillsides with a altitude which ranges from 825 to 1300 feet (250 to 400 meters) above sea level. Some of the vineyards face the plain of Prato, others the Arno river valley. Precise and binding rules now insure high

quality by limiting the production, even though the wine is much in demand. But the name Carmignano on the label is now well known in foreign markets, even across the seas. But these wines already had a certain reputation in England during the Renaissance thanks to the efforts of the Medici.

Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici, the author of the famous edict of 1716, customarily offered several bottles of Carmignano to England’s Queen Anne. At Artimino, where he had improved the cultivation

by filling up and draining humid areas, he produced “extremely elegant and choice wines which he sent to all the courts of Europe”. This is recounted by an anonymous monk, in a work praising the Grand Duke. And in London, during the second half of the eighteenth century, the wines of Carmignano were imported and distributed by Filippo Mazzei, a native of Poggio a Caiano. Shortly afterwards, this illustrious personage emigrated to the United States to fight at the side of the Americans in their war for independence. And he also transferred to the new world some of the vines of his birthplace and the famous dried figs of Carmignano as well. In Virgina, Mazzei became known as an agricultural expert and counsellor to Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. The president became so familiar with the wines of Carmignano and Artimino that he even included them in his own private cellar. In the 1880’s, the cellars of Ippolito Niccolini exported these wines to Switzerland, Germany, and the

Austro-Hungarian Empire. And such was the success that, at the first years of the twentieth century, foreign markets absorbed two thirds of the entire production of the firm, particularly after the conquist of the English and the American by Marquis Antonio Ricci, who had inherited an estate at Castello. Long processions of carts and carriages, loaded with casks and wooden packing cases, thus departed every day from the Niccolini cellars almost on a daily basis for the railroad station of Carmignano.

According to the written testimony of Filippo Mazzei, the wines of Carmignano, unfortunately did not stand up well to the rigors of long ocean voyages, unlike the wines of Burgundy and Spain which, on the contrary, suffered no damage and even improved during the period in which they were transported. Villifranchi says the same thing, when describing the wines stored in the “cool, deep cellars” of Filippo Cremoncini. But these defects were soon remedied, otherwise the success of Carmignano in foreign markets would be inexplicable.

These, sipped at the proper moment, were unquestionably “the loveliest, most delicate, and well preserved wines which can be drunk”, and were prepared with grape bunches which had been set aside to dry in the sun, unlike Chianti, which reinforced by must. The wines “aged well for two or three years, as long as they remained in the same place and did not undergo long voyages”.

In fact, as soon the practice of the “governo”, of adding new must to wines which had already fermented, was abandoned, or at least drastically reduced, “results were excellent”. These are the words of Filippo Mazzei who, not without some difficulty (and paying a higher than usual price for the times for the wine), succeeding in convincing Cartei, a cultivator at Carmignano, to work according to his instructions. This demonstrates that tradition is not, as certain authoritative producers maintain, something fixed and immutable. Nor has it ever been. Wine is a mirror which reflects the mind and spirit of those who inhabit the world where it is produced.

Not all the wines, however, seemed to suffer from this type of seasickness. The “wine of the area of Artimino”, which Villifranchi distinguished from that of Carmignano in 1700, was famous for its excellence and for the presence of unusual grapes in the blend, many from Spain, and was exported to Germany and England precisely for its capacity to stand up to transport and “still be able to age and improve” for another eight to ten years.

And so experiments – such as the use of small barrels of French oak during various phases of the fermentation and aging of various minor varieties of the zone in order to bring out all of the aromatic qualities of the grapes – are most welcome. As are the recovery of other old peasant traditions. And there are those who, today, avoid using Trebbiano or other white grapes in the Carmignano blend (allowed in the appellation’s production rulesup to a maximum of 10%), another return to the past. As long as the wines maintains the typical characteristics of the Carmignano we known. But the producers themselves are the first to make this a priority.