A Guide

The wine museum, hall by hall

The Museum of Vine and Wine in Carmignano is undoubtedly a wine museum attempting to tell the story of wine moving through panels which are the result of a careful research in a sort of illustrated story. The wine also becomes an excuse to tell, in turn, of the people who live and have lived in Carmignano, about their history and culture. It’s a museum of the territory: or “terroir”, as they better say in French. Possible start and end of each trip to Carmignano.

The Museum of Vine and Wine in Carmignano is undoubtedly a wine museum attempting to tell the story of wine moving through panels which are the result of a careful research in a sort of illustrated story. The wine also becomes an excuse to tell, in turn, of the people who live and have lived in Carmignano, about their history and culture. It’s a museum of the territory: or “terroir”, as they better say in French. Possible start and end of each trip to Carmignano.

In the museum, quotes about the wine of Carmignano by famous and unknown writers, painters and poets, come in succession. Here are the

Etruscans and the Romans with their craters left in the cemeteries scattered all throughout the Montalbano, here are the Middle Ages with the bright ceramics from Bacchereto and the sharecropping which effectively redesigned and shaped the landscape of our region, here is the Swiss ethnologist Paul Scheuermeier who, in the first decades of the twentieth century chose Carmignano for his research which is exemplifying and peculiar at the same time. And then the banco of the Grand Duke Cosimo III de ‘Medici in 1716, the first example in the world of designation of origin ahead of its time (it came more than a century before the French AOC), the appreciation by Datini, the merchant from Prato, in the fifteenth century, the wine that was exported to foreign countries, the intuition of Filippo Mazzei in the middle of the eighteenth century to reduce and cancel the government practice and get rid of the “seasick” of the Carmignano wine (which would be successful in England), the quote by D ‘Annunzio and the old Niccolini cellars.

In a museum of vines and wine, located in a land still particularly suited to wine, one can’t miss the connection with the times we are experiencing today and modern techniques. The link is in the windows in the first hall and in a multimedia CD by Ugo Contini Bonacossi and Luciano Ardiccioli.

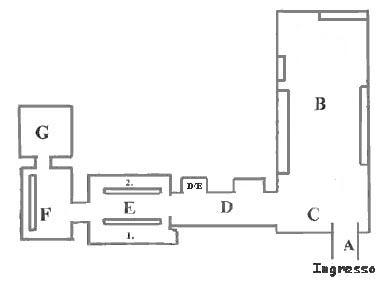

A.

The entrance to the Museum overlooks the central Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II. The narrow corridor that the visitor has to walk through gives the sensation of crossing the rows of a virtual vineyard, immersed in a timeless dimension. On the walls there are in fact two works of Bartolomeo Bimbi (1648-1729) preserved in the nearby Medici villa in Poggio a Caiano. The panels, which represent respectively 37 and 38 different types of grapes, inform us on what vine varieties were grown there at the time (some are long gone) and suggest that over the centuries there has also been a continuous evolution and research in this field.

B.

From the entrance we get to the first hall. No better place could be chosen for a wine museum . Vaults and floors made of terracotta full of history, the ones you walk through are part of the former Niccolini cellars, a historic winery from Carmignano which was located in the building that still today overlooks Piazza Matteotti (just above the Museum), next to the town hall and from which, in 1880, the barrels of wine destined to Switzerland, Austria-Hungary and Germany departed . You can find an old picture of the company in the penultimate room. Entering this first hall on the right wall, visitors find a selection of current local wine production, in front of a cabinet with oenology books and parts of the Melis collection, eight hundred bottles from all around the world collected by this historian of economics with a passion for Datini from Prato and wine.

There are tables for the tasting evenings, a large screen for watching videos and a multimedia corner. Among the videos available in the archive of the museum there is also a series of interviews with elderly peasants made since the eighties by the municipality, in collaboration with Giovanni Contini from Soprintendenza Archivistica della Toscana: the testimonies tell of Carmignano as it was and old crafts which no longer exist.

C.

Returning to the end of the initial corridor there is another long hall, from which, as in a sort of illustrated tale, the true story of Carmignano wine begins. This is preceded by panels on the history of the containers used to store wine: the Etruscan cratere, the orciolo, the typical caned flask. Several panels with agricultural tools are scattered here and there. Once there was also a table set like a mediaeval canteen with ceramic tiles reconstructed on the basis of the finds in Bacchereto, which between middle Ages and the Renaissance housed many famous furnaces. One belonged to Leonardo da Vinci’s grandfather. Those findings will be exhibited in a museum specially dedicated to them which will be soon opened in Bacchereto.

D.

The journey continues and we go beyond some other milestones. In the small niche the panel on the right tells of the significance and the important history of the Barco Reale, the huge Medici shooting ground which also gave a name to a wine and which in fact was taken as a reference to mark the boundaries of the production of Carmignano in the announcement of Grand Duke Cosimo III de’Medici in 1716, the first certificate of nobility that came more than a century before the famous French AOC. The stone wall surrounding it was 52 kilometres long and up to two metres high, guarded by game wardens. In front of the panel an ancient wooden wine press from the seventeenth century. In the corridor on the left there is a long series of “cabreos” and old maps of farms, some of them still existing, describing the metamorphosis of the territory and the action on it by humans who have given it its shape by cultivating it. A plate divided in half (but the two halves, on closer inspection are not exactly the same) reminds us of the historic agrarian contract that has characterised our agriculture from the end of 1700 until the eighties.” The share cropping, which, dividing the harvest between owner and labourer was an incentive to greater productivity,” as some landowners say today “in the fifties and in the sixties it was also, for some, a school of economics to the point that some farmers and sharecroppers have become textile entrepreneurs.”

D/E.

In the doorway a glimpse of Vinsantaia with its typical reeds is depicted.

E.

Hidden under the wine and the agriculture of Carmignano there are also stories of people and places. Paul Scheurmeier, Swiss ethnologist, collected them from 1919 till 1930 for the Linguistic and Ethnographic Atlas of Italy and Switzerland, deeming Carmignano peculiar in many respects but also emblematic of many other farming communities in Italy.

1. The third hall on the left side is completely dedicated to him and that research on everyday life and rural culture, its customs, tools and equipment, which led him to travel central and northern Italy. In Carmignano Scheuermeier took 63 photos. Among them the best ones dedicated to the cycle of vine cultivation and wine production have been chosen and placed on some large panels next to the original captions translated from German and drawings, which are numerous too, by his collaborator Paul Bosch. In front of those images, in the glass cases and on the walls, you can find a few of those old farm tools photographed.

1. The third hall on the left side is completely dedicated to him and that research on everyday life and rural culture, its customs, tools and equipment, which led him to travel central and northern Italy. In Carmignano Scheuermeier took 63 photos. Among them the best ones dedicated to the cycle of vine cultivation and wine production have been chosen and placed on some large panels next to the original captions translated from German and drawings, which are numerous too, by his collaborator Paul Bosch. In front of those images, in the glass cases and on the walls, you can find a few of those old farm tools photographed.

2. On the opposite side of the room with a deliberate contrast between coloured and black and white placed so as to be symmetric to each other. There are some more recent photos which are the result of a research on the world of sharecropping on the wane by Vittorio Cintolesi between 1980 and 1990. It’s a journey to his homeland and among memories. Fragments of poems, short stories and essays by Hesiod, Cato, Marone, Tibullus, Gilgamesh, Mahabbarat and Leonardo da Vinci have been chosen to function as captions to those snapshots. That as if to suggest and demonstrate that those images, those techniques and instruments portrayed, as well as the cultivation of the vine itself, have roots that go deep back into millenniums and branch out in more parts of the world. Mediterranean scenes of different worlds and eras, along a time span of a thousand years, which are often incredibly identical. A panel with photos and quotes by Cintolesi is also located in front of the winepress seen before.

F.

The fourth hall is a kind of virtual library: a continuous citation of unpublished archival sources and bibliographic research, and an incentive to further research. The sense is to demonstrate how the Carmignano wine was appreciated and honoured in the past, but also to highlight its peculiarities about the composition of the vines as well as its history and metamorphosis. A very important milestone: the announcement of the Grand Duke Cosimo III de ‘Medici in 1716, which for the Carmignano wine (together with the Chianti Valdarno and Pomino) established precise and strict production standards, which in fact anticipated the contents of today’s DOC and DOCG which the same wine would achieve in 1975 and 1990.In the room there is also an old and small mill for flour, as well as references to two other important and historic cultures of this region: figs (dried and paired in a very special way) and the olive tree with its also very appreciated oil.

G

The last hall, which we can only view, houses other bottles from the private collection of the historian of economics Federigo Melis, who, during his travels around Italy and Europe (and even beyond) gathered hundreds. As a whole there are more than eight hundred, some cases even a century old.

(from a text by Walter Fortini)